- Home

- Anne-marie O'connor

Star Struck Page 14

Star Struck Read online

Page 14

Catherine was going out, Andy knew. She would go into the next day her spirits high and she would be sent home crushed, to deal with her sick father and to watch the others on the TV living the life that she had a chance at if she’d only pushed herself forward a bit more.

‘She has got a story,’ Andy blurted. He knew he shouldn’t be saying this, it wasn’t information about his own home life that he was divulging, it was a girl he barely knew who had entrusted him with a secret, but if he didn’t say something now she was going home.

‘She hasn’t, Andy, I asked her,’ Richard said, as if Andy was becoming tiresome.

‘Her dad’s got cancer,’ he blurted out.

Richard thought about it for a moment then said, ‘Well, it’s obviously not something she wants anyone to know about, otherwise she would have told me, wouldn’t she?’

‘And depression. And she’s been his carer for years. And she practically raised her younger sister.’

Richard looked at his wife with a glint in his eye that suggested that they may have struck gold. ‘What do you think?’

‘I think that if we run the VT of her dad bursting into the room and then we find out later that he has cancer then we have a genuine human interest story. People will watch Catherine because they’ll really care about her. Beats whatshername with the mother in the clink.’

Richard thought about it. ‘I’m not sure. She needs to be more honest with us.’

‘That’s true,’ Cherie said, ‘But I don’t think that you confronting her now is a good idea, Richard. You forget that you put the fear of God in people,’ Cherie said. ‘Give her a little bit more time to think about it.’

‘The fear of God?’ Richard asked, looking to Andy for confirmation.

Andy gulped. ‘Er, you are a bit scary sometimes.’ Andy silently berated himself for sounding like a minion. He coughed, ‘But with regards to Catherine,’ he said trying to regain his composure, ‘put her through and I’m sure she’ll tell you. She just needs to trust people. It’s not something you want to admit straight away to the entire nation.’

Richard looked at him as if he didn’t quite understand what he had said. Of course, Andy thought; people throw themselves at Richard every week, opening up about the most painful episodes in their life, just to get a taste of fame. He didn’t think Catherine was like this somehow. Andy was worried. Catherine could never know that this meeting had taken place, but if she didn’t admit what was going on at home, she might find herself back there far sooner than Andy hoped. He had to get her to say something or he had to get Richard to give her a chance. He wasn’t sure which was the easier option; he didn’t fancy either.

‘I’m sorry,’ Richard said, shaking his head, ‘We can’t put her through on the strength that she might, one day, want to tell us her story. It just won’t work.’

Cherie sighed. ‘I disagree,’ she said.

‘Well, that might be the case, my sweet,’ Richard said, demonstrating with dripping sarcasm that he definitely wore the trousers in their working relationship. ‘But it’s not going to happen.’

Andy’s heart sank but he shrugged and said, ‘OK that’s fine.’ What else could he say?

‘What’s up with you?’ Mick asked.

Why the bloody hell have I agreed not to say anything to Dad? Not even agreed, actually come up with the idea? ‘Nothing.’ Jo said trying to act casual when what she really wanted to do was take her dad by the hand and ask him what was going on.

‘You’re perched on the chair peering at me. It’s unnerving.’ Mick huffed, not taking his eyes off the Saturday TV offering.

Jo stood up quickly as if that somehow negated her perching and peering. ‘Can I get you a cup of tea?’ she asked.

‘Why?’ Mick shot her a look.

‘Why? Because I’d like to.’

‘Why would you like to?’

‘Bloody hell, Dad, I’d just like to, OK?’

‘Two sugars.’

‘I know you take two sugars.’ Even with the knowledge that her dad had cancer, Jo couldn’t help being short with him. He was unbelievable.

‘Well, it’s that sodding long since you’ve made me one that I thought you might have forgotten.’

Jo bit her tongue. ‘OK. Two sugars,’ she said, marching into the kitchen.

Jo put the kettle on and stood looking out of the kitchen window into the back garden. It had been a warm summer’s day and the sun was just setting behind the trees. The back garden hadn’t changed since Jo was a little girl. It was only a small patch of grass but as kids it had been big enough to play a game of two-a-side and to put their blow up paddling pool in on days like today. The garden was overlooked to one side by the next-door neighbour in the adjoining semi, an old lady called Ann (Spitting Annie, Mick called her, on account of her bad dentures and his claims that she left him drenched every time he spoke to her). To the other side there was a tall fence and the old garage which Mick used to house all sorts of rubbish that was one day – if he was to be believed – going to make him a small fortune at a car boot sale. The garden of 16 Verdun Road, Flixton was further enclosed by a tall wrought-iron gate and was a safe secluded oasis from the hustle and bustle of the rest of the world, which, to a child living on a main road, seemed to begin at their front door.

Jo looked down at the mug that she had pulled from the cupboard and the teabag that she had thrown into it. There were large splodges of water surrounding the cup and in the teabags. Jo realised that she was crying. She grabbed some kitchen roll and dabbed her face. Suddenly the back door flew open, making her jump.

‘If I get another pissed bloke asking me if I want to join the mile-high club, I’ll fucking scream,’ Maria said, throwing her overnight bag into the kitchen and slamming the door behind her.

‘You’re not on the flight long enough to get as high as a mile are you? I’d have thought it was more like the forty-foot club.’ Jo had to be quick-witted. She couldn’t let Maria see that she was upset and if she hadn’t immediately slagged her off as she walked through the door, Maria would have known that something was wrong and Jo really couldn’t face a conversation with Maria about her dad. She needed to keep this to herself until Catherine got back. It was Catherine’s call as to when and how they confronted Mick about his illness. Anyway, Maria would only make a huge drama out of it and make matters worse.

‘I’ve been working in Premium Economy I’ll have you know,’ Maria said witheringly.

‘What d’you get in Premium Economy? Packet of peanuts and a life vest?’

‘Shut your face …’ Maria began, but then noticed something. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Making a cup of tea.’ Jo said, without catching her sister’s eye.

‘You don’t drink tea.’ Maria’s eyes narrowed.

‘It’s for Dad.’

Maria was on Jo like a velociraptor spying its prey. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

Nothing.’ Jo snapped, mashing the teabag at the side of the cup and pushing past her sister to get to the pedal bin.

‘What’s up with him?’ Maria said, closing in.

‘Nothing’s wrong with him. He’s watching Martin Clunes Sings Abba in there. I was going round the twist so I decided I’d be nice to him and make him a cup of tea.’

‘You’re never nice to him.’

‘I am today.’

‘Something’s going on.’

‘Nothing’s going on. Not with us. You on the other hand …’ Jo said, trying to divert attention away from her and her dad.

‘What?’ Maria asked puzzled.

‘Have you got jaundice?’ Jo asked innocently.

‘No, you cheeky cow, I’ve had a spray tan.’

‘You look like an Oompa Loompa.’

‘I do not!’ Maria shouted in horror. She ran from the kitchen and thundered up the stairs to check the damage.

Lucky escape, Jo thought. Maria would spend so long inspecting herself in the mirror that hopefully, by the time she

came back down, she would have forgotten about the cup of tea and Jo could lie low. Then all she had to do was try not to say anything to her dad until Catherine returned. Unless he seemed to be suffering in any way and then she was stepping in, promise or no promise. She didn’t know what she would do or say but after a moment’s thought she knew that she’d do what she always did – cross that bridge when she came to it.

Catherine’s nerves were in shreds. Forty-eight hopefuls had walked into the audition room this morning and twenty-four would be going home. Catherine had been given ‘The Power of Love’ by Jennifer Rush to sing at this morning’s auditions. She wasn’t a massive fan of the song but she had practised it in the small practice rooms at the far end of the manor. This afternoon, though, they had to pick two of their favourite songs to sing and Catherine had been toying with a number of songs in her head, but she kept coming back to material that she had written herself. She didn’t know what the Star Maker policy was on singing their own songs. Catherine was sure there was some complicated reason why it might be frowned upon but she thought that she’d just go ahead, sing the song and worry about it later. It was her voice that they were interested in surely, not the song that she chose. Catherine loved writing songs and she felt that the songs that she wrote suited her voice well, whereas with other people’s songs she often felt as though she was pretending to be someone she wasn’t. Not that she minded singing some of the greatest songs ever written, it was just that her voice was so specific in timbre that she couldn’t belt out huge bursting show stoppers like Kim could. She preferred sweet, heartbreaking songs.

The judges filed into the room and the air around her suddenly tightened. This was serious now and everyone felt the change in atmosphere. When there were four hundred people in the room it was still exciting, but the prospect of getting through felt vague and distant. Now it was a distinct possibility for the people in this room that they would be one of the twelve through to the New York finals of Star Maker. Catherine looked around and wondered who in the room would win and would no doubt go on to be a huge recording artist. Her gaze fell on Star. It would probably be her, Catherine thought wearily. As irritating and utterly charmless as she was, she was the sort of person that people talked about. Catherine wasn’t. She didn’t stick in people’s heads. She was one of those people that old acquaintances said, ‘How are you?’ to while they racked their brains for a name.

Catherine sat down next to Kim and listened as Richard Forster gave them all a pep talk. She was getting used to the pattern of his inspirational speeches. The poor man, he probably didn’t know what day of the week it was. He had arrived in from LA two days ago and was due in Chicago in two days’ time. He was responsible for not only fronting Star Maker in the US and the UK but executive producing the show in twenty different countries. He probably gave these ‘Give it your best’ speeches in his sleep. As Richard Forster received rapturous applause and whoops from the remaining forty-eight – something else he was probably so used to that if he wasn’t whooped and hollered at least twice a day he probably wondered what was wrong – Catherine felt a tap on her shoulder. She turned around to see Andy smiling at her.

‘Hi!’ she said enthusiastically.

‘Everything OK?’ Andy asked. He seemed to be matching her enthusiasm.

‘Yes, fine. Just nervous. You know.’

‘Course.’ Andy said sitting down. ‘You OK about last night though? Your dad, I mean.’

‘Yes. I’m sorry about that,’ Catherine said, looking down at her hands. ‘You caught me at a bad moment.’

‘It’s OK. You shouldn’t keep it bottled up you know.’

Catherine laughed drily, Andy didn’t know Mick Reilly. ‘If I told anyone my dad would go spare. He’s going to hit the roof when he finds out Jo knows, never mind anyone else.’

‘But you could tell people here … if you needed to.’

Catherine looked up, confused. ‘Why would I need to?’

‘Well, you wouldn’t, but I’m just saying they’re all really supportive and kind here and everything and if you needed to tell people, well you could …’ Andy trailed off as if he didn’t really believe what he was saying.

Catherine looked at the ruthless Richard and his waspish wife Cherie and the Star Maker crew who were sitting around all enjoying their jobs but very much there for themselves and thought that this was definitely an odd thing for Andy to say.

‘Right OK, I’ll bear it in mind.’

‘Good, yes, do,’ Andy nodded emphatically. ‘Anyway …’ He paused as if he was plucking up the courage to say something.

‘Yes?’ Catherine looked at him half smiling, half wondering what he was going to come out with next.

‘I was just wondering and I’m rubbish at this,’ Andy’s cheeks flushed red. ‘There we go, right on cue, red cheeks …’

‘I get that too. It’s awful, isn’t it?’

‘It certainly is. It makes you feel like everyone can read your mind,’ Andy said touching his face.

‘That’s what I think!’ Catherine said, agreeing excitedly.

‘Everything all right at the back?’ A voice bellowed from the front of the room. It was Richard Forster.

‘Sorry, yes, everything’s fine,’ Catherine said, her face burning brightly. She looked at Andy and the redness of his face and they both tried in vain to bury their laughter.

‘What a pair,’ Andy whispered.

They quickly composed themselves and everyone went back to listening to the person auditioning. When Catherine felt that the attention was definitely off them again she looked at Andy. ‘What were you going to say?’ she whispered.

‘I was going to ask if you’d like to meet up with me for a drink sometime?’

‘Really?’ Catherine felt herself redden again. ‘A drink?’

‘A drink, a date, whatever.’ Andy felt flustered. ‘No pressure.’

Catherine smiled at him and did something that her usual self would never do. She grabbed Andy’s hand and squeezed it. ‘I’d love to,’ she grinned.

‘Catherine Reilly!’ A runner that Catherine didn’t recognise shouted. It was the third time that day that she had been called to perform in front of the judges but she still reacted like she’d been shot when her name was called. Catherine’s heart thumped heavily as she got to her feet. ‘Good luck.’ Kim whispered. Catherine’s bum was numb from all of the sitting around and waiting. She had got off to what she considered to be a shaky start that morning with her rendition of ‘The Power of Love’. It was a big song that required a big voice. Catherine had tried to give it her own interpretation but the judges didn’t seem too impressed. Richard had said that it was a ‘little reedy’ for him. Catherine wasn’t altogether sure what that meant, but she knew it wasn’t good. Her second performance, an hour ago, had been ‘The Wichita Lineman’ by Glen Campbell. Richard Forster had sat up in his chair after the performance and said, ‘Well, Catherine, I can see a lot of blank faces here, whose music knowledge starts and stops at “Angels” by Robbie Williams, but that is one of my favourite songs and that performance was great. You’re back in the race.’ Catherine had breathed an enormous sigh of relief and returned to her seat.

There were other girls in her category that Catherine thought had performed better than her over both songs. One girl called Julie had given a particularly brilliant performance of ‘Gimme Shelter’ by the Rolling Stones and then had received a standing ovation for her interpretation of ‘Daniel’ by Elton John; she was bound to get through, Catherine thought.

Catherine stood up and walked towards the stage. She didn’t think she’d ever get used to the utter dread that she felt as she went up to perform in front of the judges. She and Kim had discussed it, they both felt the same. Star didn’t seem to suffer from nerves, she just glided up, performed, thought she was brilliant and then sat back down again.

‘And what are you going to sing for us, Catherine?’ Lionel asked. The judges took it in turns to speak to

the hopefuls at they came up to sing. Andy had explained that they strictly rotate who does the talking and that each judge was contractually obliged to speak for a certain amount of time. This was so that no one judge received more airtime than another. This, of course, didn’t include Richard. He was above joint and equal contracts. He ran the show.

‘I’m going to sing a song called “The Sleeping Man”.’

‘And who’s that by?’

Catherine was about to admit the truth, that she’d written the song, but she bottled it at the last minute, knowing that Richard would probably have something to say about her singing her own work at this crucial stage in the competition.

‘Mary Devoy,’ Catherine said confidently, giving her grandmother’s maiden name.

‘Who?’ Richard asked.

‘She’s an Irish singer,’ Catherine said matter-of-factly.

Lionel nodded confidently as if he’d been listening to this Mary Devoy character all of his life.

‘Off you go,’ Richard said.

Catherine began to sing. She couldn’t believe she was singing one of her own songs. She had sung this a thousand times in the church and in her head at work as she had sat at her desk waiting for the next call to drop through into her headset. When she finished the ballad she looked out at the judges.

‘Thank you, Catherine, that was truly great,’ Lionel said.

‘Beautiful,’ Carrie agreed.

‘You had a shaky start this morning, Catherine, but that was sensational,’ Cherie said nodding her head emphatically.

Catherine looked at Richard, looking for his definitive seal of approval. He was scribbling something on a piece of paper. ‘Well, I don’t know who this Mary woman is, but she should get out of Ireland more often. That song was great.’

‘Thank you,’ Catherine said, quietly buoyed by the praise but hoping that she hadn’t just jeopardised her chances in the competition.

She walked back to her seat, taking her place next to Kim. This was something you didn’t see on the TV – the waiting. They sang for maybe ten minutes each a day but they spent at least ten hours waiting around. Not that Catherine minded but if she had known she would have brought a book. On TV it always looked so fast and frenetic. Even the off-the-cuff quips that Richard Forster dished out were repeated so that the producers made sure they had the best shot of him delivering his cutting comments. One comment that morning – when Richard has said that a girl sang like Johnny Vegas in a frock – had been picked up by the producers and had to be repeated twenty times, with the camera circling Richard until they had it from all angles. The whole thing had taken an hour and the poor girl had had to stand on the stage and react every time the remark was repeated. At the beginning she had been crying; by the end she was simply rolling her eyes and willing them to just get on with things.

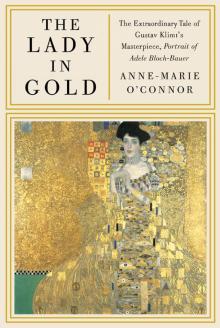

The Lady in Gold

The Lady in Gold Star Struck

Star Struck